Fiction | November 28, 2020

Whatever It Takes

An alternative account of the events of Friday, March 22, 2019.

Alex was a master of the coffee nap. Despite her worn-down state, she could gauge the depth of her exhaustion in precise degrees of caffeine. Three to be exact. A triple-shot of espresso would be enough to nudge her awake after ten beautiful minutes of sleep.

Her home office was furnished with a pristine espresso machine, which stood proudly as the bastion of her productivity. Although her skill with the Swiss-made instrument was by no means impressive, the shots she pulled still surpassed what passed for “joe” in her adopted country. Bad coffee was just one of many indignities that America inflicted on her Continentally-raised palate—a disgusting substance whose only redeeming quality was convenience.

But the espresso machine was out of commission that night, waiting on parts that she had ordered the week before. Instead, she walked over to the refrigerator in the kitchenette and cracked open a bottle of cold brew. It was as if lowering the temperature had induced a phase transition, transmuting what was once non-ingestable into something more tolerable. The cold numbed her tongue to the taste as she forced down the mud-brown liquid. Having flooded her gullet with sufficient stimulus, along with a few tea biscuits, she stumbled onto her bed. The cool spring night was bleeding into dawn, and the birds perched outside of her bedroom window were already calling in the new morning. Without a care for them or for the world, she lay flat on her belly and slept.

Alex dreamt that she was flying under a moonless sky. Her arms dangled loosely in the shape of a V, passively generating lift. Flying felt much like swimming, she thought, without the exercise. She was searching for her companions, a flock of albatrosses that had merged with her not long ago, but they proved difficult to spot in the rolling fog. The birds had simply melted away into the murkiness of the sea mist.

Though nowhere seen, their wingbeats reverberated through the moist night air, leaving an audible trail to follow. She cocked her head to triangulate the source of the sound, which seemed to arrive uniformly from every direction. It was then that she realized that the sound came directly from above her. It was a balmy night, she observed. Her feathery friends were probably circling overhead, riding the rising thermals over the sea. She kicked her feet out for an extra burst of speed and took off in a corkscrew. Their wingbeats grew louder as she climbed higher. Her hair was whipped wildly around, its strands dancing from her scalp, as she rounded each coil of the spiral.

The air erupted into a chorus of birdsong when she finally shot out from the sea fog, greeting her late arrival to the party. Inundated by the raucous welcome, Alex fell into a daze—the moonless sky a starry tapestry above her head, the mist a damp carpet below her feet.

Yet there was a small detail that bothered Alex and interrupted her suspension within the moment. The albatrosses, their beaks opening and closing in rhythm, warbled in the familiar chirping of tree-bound sparrows rather than the shrieking calls of roving seabirds she expected. As pinpricks of starlight widened into glimmers of sunbeams, she realized that they were not chirping hello, but rather goodbye. Perched on the threshold of wakefulness, she hesitated, wanting just to stay a little longer in the world of her dreams.

It was then that she stalled.

Suddenly, the wind no longer whipped against her face. Waving wildly, she tried to latch onto the invisible currents that had carried her up, but their slippery strands simply parted at her fingertips. The chirping of the birds grew to a fever pitch as they gawked in horror.

Alex plummeted straight into the depths of the fog, screaming as she contemplated the horror of slamming into the ocean at terminal velocity.

But the pain never came. There was no splash. Not even a sense of where atmosphere ended and water began. At the end of her descent, she found herself floating atop a shadowy, endless pool of water. Alex scratched her nose and looked around. The fog and the birds were all gone, leaving behind an immaculate sunrise.

“Wo ist alles hin?” she whispered.

The ocean murmured back in reply.

Brrrrrrrrr

It was the murmur of eddies toppling over each other across the mirror of water.

Brrrrrrrrr

The whirring of the printer woke Alex up. Without reaching for her phone, she reckoned that she had managed to oversleep on a workday. But that was not her immediate concern. Looking over the edge of her pillow, she could read the thin, squinty letters on the printer’s small LED screen, which announced that a fax transmission from an unknown sender was underway. Strange, she thought. She did not remember ever configuring her desktop inkjet to receive faxes. Yet it continued to eject what appeared to be scanned pages from an ancient document into an accumulating heap of paper on the ground.

When the LED screen finally blinked off, she stepped into her slippers to gather and collate the mess.

The document was a typewritten monograph that bore the nondescript title, A Review of Anticipatory Systems, with no author indicated. Alex had seen the term before in graduate school, when she was completing her doctorate at Stanford’s Department of Economics. That was where Williams, her previous upperclassman and current boss, had also went. Anticipatory systems theory was just one of many intellectual rabbit-holes she had indulged in outside of her main academic tack. It brought back memories, both fond and otherwise, to see it again.

While thumbing through the sheaf of papers, she saw that pages seventeen and eighteen were missing.

Alex circled the room and then checked underneath the bed. There they were, along with a printed note.

Dear Alexandra,

Please come to Eccles Conference Room 3C today:

3:00 PM March 22

Tell no one else about this.

—Jay

She wondered if the message was actually intended for her. It could also be an elaborate prank, she reasoned. Her profession attracted the ire of online cranks who wished its practitioners (mostly metaphorical) harm. But if this Jay were actually that Jay, this invitation would be a direct order from her boss’s boss—the chairman himself—that she could not ignore.

It was almost noon. She checked her notifications. Twenty-seven minutes ago, a colleague had asked her where she was and if she could look over his data analysis after lunch. Biting her lip, she tapped out a terse reply.

I apologize for the short notice. But due to a personal emergency, I will not be in the office today.

I will still be in contact through email. Feel free to call my cell if you need me urgently.

Regards,

Alex

She hit send on the message and shoved the Review into her backpack. If she were to honor this summons, she would have to leave now. It was presumptuous of “Jay” to ask her to simply drop everything and hop on the next train from New York to DC, but she would oblige. What bothered her was not the abruptness of the request. It was the mystery of it, which tortured Alex with her own native sense of curiosity.

Williams glanced downwards at the small table in front of him. Both his MacBook and a half-eaten Café Acela sandwich competed for his attention. He sighed, shutting the laptop’s lid so he could finish his meager meal in quiet communion with the other solitary Amtrak riders. It was not like he could prepare materials for a surprise meeting he knew nothing about anyway.

All he had to go on was the anonymous document tucked under his arm. The chairman had referenced it during their conversation earlier.

“Did you read it?” the chairman had asked. “The Review?”

“You mean the one you handed to me on Tuesday? Yea, I did. It’s… strange.”

Although some of the mathematical notations were unfamiliar and, in some respects, archaic, every sentence of it was sharply written, even if not immediately comprehensible. Having perused it multiple times, he still could not follow every single one of its threads. Its quizzical nature reminded him of Alex, whose keen wit had mesmerized him since their Stanford days—a secret but purely intellectual crush on his part.

“Good, good.”

“Why do you ask?”

“Come to the usual meeting room as soon as possible and you’ll find out soon enough. I’ll be waiting.”

“Sorry, I’m not in town anymore. I’m back in my regular office now.”

“Oh, my apologies. I thought you were planning to stay for a bit to sort out the rest?”

“I really did want to, but I had to return. Say, could we do a conference call instead?”

“No. I need to speak to you in person. Just you and me.”

“Three then. I can make it to you at three.”

“Okay, I’ll see you then.”

“Anything else?”

“That is all. Goodbye.”

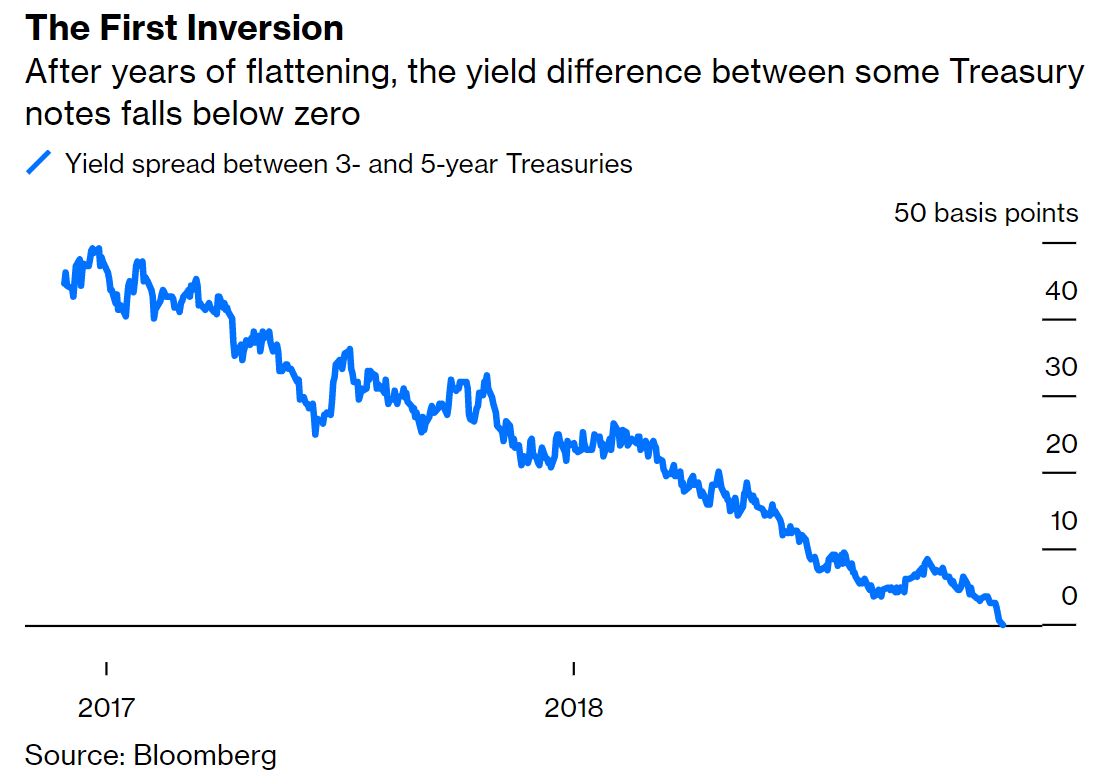

It was already an inauspicious morning. The ten year had just dipped below the three month tenor, and the chairman’s unexpected phone call lent the yield curve inversion an almost sinister edge. Were the two things somehow connected? He rejected the idea. Curve inversions were something for traders to fret about. Surely there were more important matters to summon him over. Matters that, for some reason, could not be resolved remotely in a conference call.

He had left DC just two days ago, having suffered through marathon discussions from Tuesday to Wednesday between the chairman, the governors, and the other regional presidents. Together, the committee had arrived at the anti-climactic decision to leave the bedrock benchmark rate untouched, along with a promise to revisit the matter in three months time. His eyelids grew heavy as he reviewed the last decade of monetary decisions in his head. It grew difficult to resist the soft lull of the drifting train.

Williams woke up just in time to see the train pull into Washington Union station. Dusting off the crumbs on his shirt, he made his way to the portico outside of the entrance of the Main Hall to hail a taxi. Everything was running perfectly on schedule. In no time, he was cruising down the length of Constitution Avenue and riding past the monuments and memorials of the National Mall.

“I’m back,” Williams whispered to himself.

The taxi dropped him off at the entrance of the Marriner S. Eccles building. Neither quite elegant nor quite ugly, the rectilinear behemoth of Georgia marble cut a striking figure against the clear spring sky. In a city teeming with ornamented symbols of power, it was perhaps only natural that the real thing would be found in an otherwise unadorned structure. To its critics, the Eccles building exuded a neoclassical boredom as unimaginative as the four floors of functionaries who staffed it.

The chairman was already waiting by the time Williams reached the conference room. The ambience reminded him of a very austere kindergarten, where each committee member customarily sat behind his or her emblazoned nameplate at the yawning oak table. At the center, of course, was Chairman Powell, flanked by Governors Clarida, Quarles, Bowman, and Brainard. Or as they knew each other—Jay, Richard, Randy, Miki, and Lael. Although their names still flashed brightly on the table, the other governors were conspicuously absent—along with all the usual observers and hangers-on inserted in the name of transparency.

“Hello John,” Powell greeted him half-heartedly, turning grim. “Thank you for coming all the way here from New York.”

“No problem at all,” Williams replied as he closed the door behind him, sealing off the room. “Nice to see you again.”

Williams mustered a smile and took his seat across from the chairman.

“I’m sure you have many questions for me,” Powell began. Even alone, he spoke with the same gravitas he applied to his media appearances—a patient voice honed for the communication of the committee’s esoteric decisions to an implacable outside world.

“Yes,” Williams nodded. “I do.”

“You work with Alexandra Ender, don’t you?”

“Yes. Officially, she’s still an intern, but she’s basically my right-hand woman when it comes to policy. Wicked sharp.” Williams stopped himself before gushing further.

“So you trust her?”

“Absolutely, we’ve known each other for years.”

“That’s good to know. I may need someone like her in the future.”

“I’d hate to have her go,” Williams laughed. “But I’d be happy to leave you her number and email.”

“No need,” Powell brushed him off. “I prefer more discreet means of contact.”

Before Williams could press further, Powell’s phone buzzed on the table.

“Yes?” Powell answered as he picked it up. “Okay, send her up to me.”

Alex ascended the spiral staircase towards the third floor, unsure what lay in wait for her at the end. The stairs brought her to a well-lit corridor. Following the signage, she arrived at a pair of broad, paneled doors. She knocked hesitantly.

“Come in.”

As she nudged the door ajar, she caught Powell’s eyes peering into her own.

“Now that all of us are together,” Powell said approvingly. “We may begin.”

“Alex?”

“Wait, John? You’re here too?” Alex looked at Williams. “What’s this all about?”

“I have just as much of a clue as you do.”

“There, there,” Powell smiled. “Settle down.”

Alex took up a chair beside Williams and plopped her copy of the Review on the table.

“Now if you may,” the greying chairman folded his hands. “I’d like to know what you thought of it.”

Alex swallowed back a lump. “I was in a bit of rush, so I could only give it a cursory read.”

“But when you were reading it for the first time,” Powell’s eyes were twinkling back at her. “Did something feel odd to you?”

Alex cleared her throat. “It felt intentionally… incomplete? I’m also not sure why this was given to me—”

“Aren’t financial systems an example of an anticipatory system?” Powell interrupted.

“Well, yes.” Alex then quoted from the opening paragraph. “An anticipatory system must have three parts: itself, a predictive model of its own future, and a mechanism to act upon itself based on that model. Examples can be found in biology, finance, psychology, and any other field concerning collective behavior.”

“But your intuition is correct. The text does conceal its true intentions,” Powell said. “The document you hold before you is the translation of an original German manuscript that was smuggled across the Atlantic from the Viennese into the hands of the New York Fed. In order to evade Axis censors, it was vital that it appeared as no more than an innocuous mathematical text.”

Not uncommon for genius to be entwined with revolution, Alex thought, and the Review certainly suggested both.

Powell continued, “I’ll briefly review its core points, just to make sure we are all on the same page here.

“Suppose there exists a network of individual anticipatory systems that interact with each other. As with any interconnected network, the behavior of each individual always depends on the behavior of the others. But for anticipatory networks, the observed behavior of the others may matter less than what that behavior ultimately reveals about the internal predictive models of the other participants. To illustrate this point, a poker tournament can be won while keeping one’s hand face down. One only needs to read the faces of other players and infer their knowledge of the game from their reactions.

Playing the players, Alex thought. It amused her to think of the chairman as a piker.

“Taking this further, an anticipatory network may sometimes be better understood as a network of models rather than as a network of individuals. To continue my analogy, if people are gambling on the outcome of the tournament without seeing either the players’ faces or their hands, they perceive the event not as a game between poker players but between different poker-playing strategies—inferred from each player’s match history—acting through the conduit of human hands.

“From the gamblers’ perspective, the strategies of each player are in every sense as ‘real’ as the players themselves. After all, the models are the ‘thing’ they are betting on and the humans merely vehicles. The perspective of the anticipatory systems analyst is much the same. The internal predictive models are as real as the underlying systems, and a network of individuals can be conceptualized as a network of models. They are duals. Fundamentally equivalent views that can be naturally exchanged for each other.

“But duals are not identical. Although systems must behave in a strictly causal way, with one interaction leading to another, models do not. The framework of causality simply cannot be applied to the ‘meta-behavior’ of models interacting with other models, because these interactions exist outside of time. To the question, ‘when did rock beat scissors,’ one can only answer, ‘whenever the rules of rock, paper, scissors were first conceivable’—now, then, and forever.

“This acausality has other consequences. Even when the myriad interactions between individuals in a crowd can be exhaustively catalogued, it is often impossible to predict their collective behavior once the number of individuals becomes overwhelming. Much like dealing with the sudden spread of an epidemic, it becomes impossible to trace the chains of causality. On the other hand, it is very easy to design games—even games with very rich behavior—that always converge on completely predictable outcomes no matter how many players it has or how clever its players are. An example is the class of games whose rules do not explicitly specify a winner-take-all dynamic, but guarantee a single winner at the end nonetheless.

“You and I know these games very well.” Powell said. “Don’t we?”

“It’s not like you to beat around the bush.” Williams was tapping his foot. “What does this all mean to us? Why was it sent to us?”

“I find that terrible things tend to happen when I speak plainly,” Powell retorted. “But if you can indulge me for a little longer.”

Alex looked anxiously between her two superiors. She had been quietly taking notes on the chairman’s words the whole time.

Powell continued, “I grant that everything I’ve said up to now sounds far removed from everyday life. And it would be, if not for the appendix on approximation theory.

“An anticipatory network as I have described is still only just an approximation of anticipatory networks in the real world. The model-system duality that follows is but a convenient mathematical abstraction. But if certain conditions hold, this approximation becomes quite good and the duality has real implications.

“For example, if we are able to gather enough people, make their thoughts and actions highly dependent on each other, and then train them such that they respond as much to abstractions as they do to realities, then something interesting emerges. When they can no longer distinguish between symbolic manipulations and physical facts, the distinction between causal behavior and acausal meta-behavior is erased.

“In such a situation the difference between prediction and action—between prophesy and future—is a meaningless one.”

Alex’s blood stirred. Everything was coming together now.

“This was the dream of Astrid Ender, who wrote the Review and arranged for its delivery,” Powell explained. “Your great-grandmother, Alex.”

“Wow,” Williams gasped, looking at her with newfound admiration.

“The Enders are a long intellectual lineage dating back to the Austro-Hungarians,” Powell explained. “Before their collapse, they were quite well-known in monetary circles. It was only a matter of time before Astrid’s descendant would make her way back into the trade.”

The two men’s scrutiny made Alex shift in her seat. Much to her relief, they quickly returned to their original discussion.

“Do you understand now,” Powell asked solemnly. “What it means to control the yield curve?”

Williams stared blankly at Powell and felt left behind. He could not comprehend how yield curve control, a newfangled policy from the Bank of Japan, fit into the picture.

“What?”

“Don’t you get it, John?” Alex said. “The yield curve does not predict central bank intervention. The change in the yield curve IS central bank intervention.”

Powell laughed heartily as he saw the flash of realization over Williams’s face. He had been waiting patiently for this moment.

“The yield curve whispers to us from the future,” Powell said. “Because my predecessors have created an anticipatory network that satisfies the conditions set forth in the Review. A machine that can pull forward the eternal future into the present.”

“You had me at acausality,” Alex said. “If I understand correctly, the treasury market allows us to send messages to our past selves.”

Powell nodded approvingly. “This is the true history of the modern Fed, born amid the flames of the Second World War. From the moment Marriner Stoddard Eccles received an anonymous manuscript in 1941. This is why we control the most liquid predictive market in the world and train a global network of traders and investors to do our bidding.”

This was all so ridiculous to Williams, but less so to Alex. She had nursed her own private doubts about the Federal Reserve’s mandate of late, opinions which she dared not air in public. The retconned creation mythology of the Federal Reserve embodied by the dual-but-actually-triple mandate had always struck her as a theologico-monetary Nicene Creed.

“The Federal Reserve acts as the eyes of the Republic to provide advance warning of threats to our democracy,” Powell said proudly. “Our stewardship of capital markets is of only secondary concern.”

Overwhelmed, Williams sank into his chair.

“The treasury market transmission network we have is still an imperfect one. Basically the financial equivalent of smoke signals,” Powell explained. “We communicate by inverting the yield curve and the information is encoded in the timing and magnitude of the inversion. Anything more complicated than that becomes garbled when you try to send messages years back in time.

“Last December, the yield spread between the three and five year tenors inverted. According to our operating manuals, this signaled that a historical-level event is about to occur at the beginning of 2020, details pending. Following protocol, we honed the resolution of our monetary antennae by gradually hiking the federal funds rate. We had to stop because the pressure on capital markets became overwhelming, but that ultimately didn’t matter. We received the main message shortly thereafter, when the three month and ten year flipped this morning.”

“Is it the Big One?” William whispered.

“Oh, there’ll be a massive deflationary shock alright,” Powell said. “But that’s not our main problem. The shock will be caused by an environmental catastrophe with global consequences. The shape of the yield curve is somewhat ambiguous because we’re not seeing things at full resolution, but it suggests that the source of the event is somewhere in East Asia, perhaps China.”

“Will there be a follow-up message?” Alex asked. “We have at most nine months to prepare and it would help to narrow down the range of possibilities.”

“There won’t be,” Powell responded. “Once we get a shock, we have to shut down transmissions and return to our role as liquidity provider, which only leaves us with enough time to send an advance warning and then the main message.”

An air of uncertainty settled in the room. Alex asked, “So what does ‘environmental’ cover?”

“It’s a fairly long list. All the way from significant astronomical impact event, tsunami, climate-induced famine,” Powell rattled off a series of scenarios, “…to a global pandemic. I’m no epidemiologist, but I’ve heard from experts that we are overdue for a flu pandemic.”

Williams and Alex sat quietly, hoping for some shred of good news.

“I’ve tried to warn the executive branch about it but the current occupants are not responding as decisively as I had hoped. Maybe they do not want to sow panic, but I am not sure. This is the first time the Fed has operated alone and there’s only so much that being the eyes of the Republic can do.”

“Does no one else know?” Williams asked.

“Other than me, the true purpose of the Federal Reserve is revealed only to the President, a few of his trusted advisors, my foreign counterparts, and previous Fed chairs,” Powell said. “And just so you know, I’m breaching protocol by talking to you both. I’m doing it because I believe that there’s a special destiny that comes with leading the New York Fed and with the Ender line.”

“Thanks,” Williams said. “But I’m not sure how I can help.”

“Me neither,” Alex added.

“To be frank with you, I’m not exactly sure what we should do either. But John, I’ve always known you to have a good head on your shoulders. And Alex, you showed resolve by responding quickly to my call. I’m sure we can work through this together.”

“Okay,” Williams agreed timidly. Powell could be overbearing at times.

“And we’re going to have to meet in person, the three of us, more often than our quarterly FOMC meetings.”

“Sure.” The weight of the country pressed on Williams’s shoulders, and the burden of long commutes to the capital gave him a sense of dread. “Whatever it takes.”

“So,” Powell asked. “Any questions?”

Alex and Williams shook their heads mutely.

“Oh, it’s getting late now,” Powell said, glancing over his watch. “Would either of you care to join me for an early supper? Some of Draghi’s proteges will be there and it would be good to make introductions. We’ll eventually need to confer with Mario to warn him.”

“I think I’ll pass, I’ve met most of them anyway,” Williams said reluctantly. “Also need some time to process all this.”

“Have a good one, John,” Powell waved.

“Yea, you too,” Williams replied, before slinking out of the conference room.

The chairman waited until Williams was out of earshot.

“I guess the Ender is staying?”

The Ender nodded, pondering her newfound importance.

Powell tilted back in his chair and propped his feet on the table. “Between you and me, I was never quite sure John would be up to the task.”

“I know what what you mean,” Alex said, stifling a chuckle. “But I think he’ll be helpful. At least I hope so.”

“Amen,” Powell quipped.

“So it’s all a waste of time then? All that discussion about the economy and quantitative easing and rate hikes and rate cuts. It’s really all just a front for fiddling with the dials on a massive time machine, right?”

“Correct.”

“Hah, no wonder it never made any sense to me. I figured you were all smarter than that.”

“Some of us,” Powell corrected. “Not everyone is in the know like we are.”

“Makes me wonder what else are you hiding.”

“Well, since you are going to have to find out anyway,” Powell hesitated thoughtfully. “There is a Plunge Protection Team.”

“That’s no secret, it’s called the Working Group on Financial Markets, isn’t it?”

“No, not that one. There’s an actual bunch of algos that manipulate equity futures at around two to three in the morning. The price action inside that illiquid window allows us to establish a parallel short-term communication system that sends messages days rather than years into the past without interfering with stocks too much.”

“Didn’t have that on my bingo card.”

“The Eccles building is large for a reason. It houses things that you cannot even imagine,” Powell winked. “And in due time, you will inherit all of its secrets.”

Those secrets were her birthright, Alex thought, handed to her across three generations.

She smiled. Was it not the highest irony then, that the Federal Reserve was so indebted to—of all people—Austrian economists?

Fin.